Reflections in Monochrome.

My Grandfather’s black-and-white TV: A Symbol of Community and Friendship

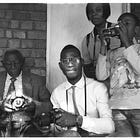

One of my grandfather, khulu's most prized possessions, an emblem of his glory days working as a chemist, was his thirteen-inch, solar-powered Telefunken black-and-white TV. At our village residence, it sat in the middle of the living room, its back a huge black box marred with many repair incisions, telling a story of an undying spirit.

Mind you, color TVs were already a normal part of our lives, and my life too. I’m not ancient. I watched colour TV at boarding school and my uncles all the time. But because Hyde Park Methodist Village wasn’t electrified, black-and-white TVs were the most apt option. Unlike color TVs where we could watch satellite channels and movies on DVD, here we were limited to whatever our only national broadcaster fed us. The youth soon dubbed the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation the "Zimbabwe Boring Channel," a fitting critique of its uninspiring content. However, as a village boy on school holidays, that black-and-white TV was my only alternative to boredom and my connection to world trends. For my grandfather, it was the news. For my cousin Lelo, it was Telemundo shows and Nigerian movies. For my cousin Muzi, Jean-Claude Van Damme and Wrestling were his picks. And, for a time, it sufficed.

Recently, after reading through a character analysis of Michael Scott, the world's “best boss” in The Office, I found myself reflecting on the idea of community and friendship. Portrayed by Steve Carell, Michael is an over-the-top character who, beneath the inappropriate jokes and lack of self-awareness, yearns for acceptance, love, and a sense of belonging. He tries, in his role as boss, to create a “family” where he feels connected, but his desperation for friendship often backfires, leaving him heartbroken.

Khulu’s Telefunken TV has come to represent, for me, what Michael Scott lacked growing up: meaningful relationships, genuine camaraderie, and a sense of belonging. This old TV—literally and metaphorically—was a gathering point, a symbol of shared experience. When the Independence Day parade was on, a family favourite, or events like the Zimbabwe International Trade Fair and national concerts, the family gathered in the living room: me, my three cousins, my sister, our helper, and friends from the neighbourhood. Together, we watched in awe as soldiers marched in the parade or as dancers and musicians displayed their highest form of showmanship. Kids sat on the floor (unless one of us dared the couch, risking a shoe thrown their way), while the adults chuckled and chattered on the sofas.

Sunday at 5 PM was wrestling night, and by 4:30, me and my friends from next door and others from the block, made certain to be bathed and ready. "No dirty feet in the living room," Gogo would remind us. During the FIFA World Cup, khulu’s friends Tshuma and Gumede would join us, jolly into the night, supporting teams whose real colours we couldn’t even see—just grayscale shades on the TV. Friday nights were for movies. My cousin would bring his friends over for action films. It usually got awkward during love scenes, and I had to pretend to close my eyes while khulu and gogo(grandmother) complained about how explicit these "white people" movies were.

Looking back, it wasn’t really about what was on TV. The social gathering was all that mattered. Those TV-watching sessions were where impromptu counselling happened, where we were given cautionary advice, and where character and vision were molded. Friendships were invested in, and it didn’t matter whose child you were—if you were in khulu’s house, you got both the beating and the treats.

Reminiscing about khulu’s TV makes me lament how friendships, community, and a sense of belonging in the status quo seem to vanish, particularly in the Western world where individualism is promoted. In a conversation with Trevor Noah, the author Simon Sinek notes that addiction, loneliness and depression can be solved by genuine friendship. Trevor echoes the same sentiments, adding that, while we invest in our health, romantic relationships, and finances, we rarely invest in building and sustaining friendships.

The question I ask myself is: who are my friends? Not acquaintances, but true friends—the people toward whom we feel emotional responsibility.

In today’s world, having something like khulu’s TV—a gathering point—is no longer sufficient. As Simon and Trevor suggest, we must be purposeful about investing in friendships. It’s not enough to assume that childhood friends or colleagues will naturally remain close. There’s a need to reach out, be present, send gifts, plan gatherings, build trust, and repeat the process. Otherwise, we risk becoming closed off, resorting to harmful coping mechanisms, or ending up like Michael Scott—desperate for acceptance, yet cynical about the world.

In a world where individualism reigns and loneliness is an epidemic, it’s not enough to rely on life’s circumstances to commune. Building and nurturing relationships must be deliberate. Akin to the TV needing constant repair to keep functioning, our friendships desire maintenance and care. Or, our friendships must exist.

So, as I reflect on my past, I challenge myself—and all of us—to ask: what are we doing to keep our communities alive? Who are we reaching out to? How are we building trust and showing up?

Because, in the end, it is through the intentionality of creating our “Telefunken TV” moments that desperate acceptance seeking is shunned, where friendships and community are not just memories but a living, breathing part of our lives today.

Please make sure Muzi reads this. He'll have a good chuckle when he reads how you detailed his affinity with Jean Claude Vann Damme